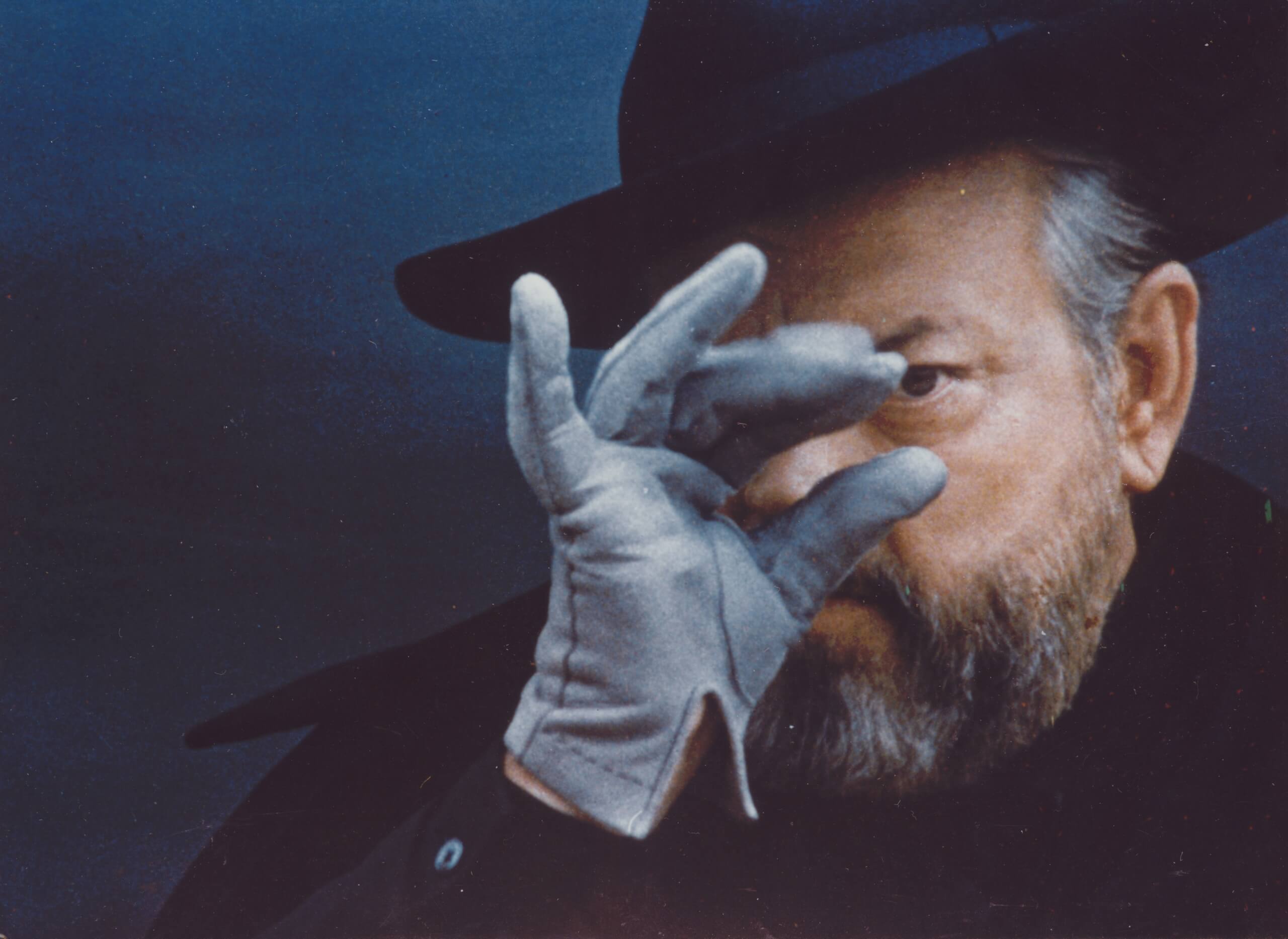

About Time: You Discovered Orson Welles at BFIBy Danielle Wood

Orson Welles was anything but a one trick pony. He was ‘a jack of all trades’ as Brits might say. For those who are familiar with his name yet can’t put a finger on the projects he was famously attached to; Citizen Kane is a notable start. From there begins an entire sloth of films he produced, directed and acted in, and this Summer the British Film Institute (BFI) are honouring Welles with a two month slot of his work in film and TV showcasing throughout July and August.

Classics such as The Lady From Shanghai, Touch Of Evil and Citizen Kane will feature on the BFI’s powerful line-up. On top of which there will be three adaptations of Shakespeare: Macbeth, Othello and Chimes of Midnight drawn from five plays considered a climax of Welles’ career. And what better time to reflect over his masterful works in what would have been his 100th birthday this May.

Welles began his career on stage and founded the Mercury Theatre in New York City; an independent repertory company that presented acclaimed works on Broadway. Then came the radio airwaves where he found national and international fame with a series of talks entitled The Mercury Theatre on the air. He turned his hand to film and rose to fame in a time when Hollywood was golden yet he wasn’t without challenges that present-day Directors face. Welles produced his films outside of the studio system therefore found it difficult to gain creative control over his projects. This is one of many instances where Welles’ nonchalant approach was to ignore mainstream instruction and follow his own path.

Citizen Kane (1941) was co-wrote, produced and directed by Orson Welles. Based loosely upon the life of William Randolph Hearst; a mighty American newspaper publisher. Herman J. Mankiewicz was commissioned to write a screenplay, after mutual agreements were reached regarding storyline and characters, both Welles and Mankiewicz wrote drafts which were later merged by Welles who came under fire for not crediting enough of the film to Mankiewicz. Welles’ honest answer to such scorn was: “naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank’s and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own.”

After discovering Citizen Kane’s dominating Hearst features, on release his media outlets boycotted the film. In the 1940’s the film was treated with trepidation. As time passed, the film has been described by film critics as one of the all-time greatest films. Regardless of all the negative chatter, Citizen Kane received nine Academy Award nominations, bagging Best Original Screenplay for Welles and Mankiewicz.

The Lady From Shanghai (1947) was intended as a modest thriller but rocketed to dizzying heights after the financier – Harry Cohn – suggested Welles estranged wife Rita Hayworth co-star. With the début of The Lady From Shanghai came initial mixed reactions from different sides of the Atlantic. While the film was well received in Europe it was not until decades later that America jumped on board. Like other Welles films, he uses his ambitious trickery to create a pivotal body of work. The closing shoot-out scene has since become a pinnacle of film noir, sketching the way for the dazzling genre.

Touch of Evil (1958) was Welles’ last Hollywood feature. A newly married couple are honeymooning in a small Mexican town when the police begin to investigate a bomb explosion. The film unfolds plots of corruption, murder and kidnapping. Welles took Touch of Evil to a higher place than many films venture to go; he transforms pulp literature into a bold expression of film.

The 1998 re-edited version of the original by Walter Murch – based on a 58 page memo Welles wrote to Universal Studio with his suggestions of alterations to the studio’s cut – will run as part of the Orson Welles BFI tribute.

Last but certainly not least, the recently discovered unfinished, unedited silent comedy film Too Much Johnson will be screened at the BFI. Shot when he was aged 23, Welles’ destiny in film was sealed with his infatuation with the latter project. He hear by made the shift from theatre to film and the rest is history.

For amateur or advanced film goers the Orson Welles series at BFI shines a light on his career before, during and after film. The triple threat boy wonder revolutionised the entertainment world. Like our beloved Hitchcock, Welles’ public bravado kept him and his works in the spotlight from prodigy star to theatre, film and TV connoisseur. He upheld his stance with guts and guile not like modern-day counterparts who flee from our sights quicker than you can say Citizen Kane.

Orson Welles: The Great Disruptor at BFI Southbank 1 July to 31 August.